In 1854 the Hebden Mining Company began to exploit the veins in Bolton Gill – a tributary of Hebden Gill, and in the next eight years it extracted 1,910 tons of lead ore worth the equivalent of £1,330,000 in today’s money. As part of their investment, they built a track up Hebden Gill including the Miners’ Bridge; a long level called Bottle Level; a 250’ deep winding shaft the head of which is still standing; a dressing floor with a large waterwheel in the floor of the gill; and a smelt mill near the Miners’ Bridge.

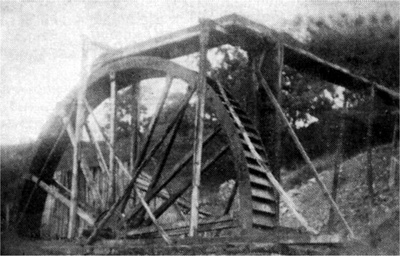

The Overshot Water Wheel about 1900

As with many mining ventures, crashes come as rapidly as the good times, and in 1862 shortly after reaching its peak, production just ceased. All the accessible ore had been extracted, and a couple of trial levels further down the valley failed to find any worthwhile veins.

As one last final push, it was decided to dig a level from the centre of Hebden village (SE 0283 6296) north-east towards what is now Grimwith Reservoir, in an attempt to intercept the veins which had proved to be so profitable in Bolton Gill. A small team worked day and night for eighteen years, pushing the level for 2,610 yards, using compressed air drills powered by a 36’ diameter waterwheel which was initially fed by a leat from a surface stream.

The level is of particular interest as it is built through the North Craven Fault belt. At some stage, the level was driven through a band of limestone and captured a considerable stream which was used to drive the waterwheel more effectively.

Unfortunately, the veins proved to be barren when they were eventually intercepted in June 1888 under Jack Cabin Top, and the project was abandoned. The lease was surrendered in 1890, and the Hebden Mining Company went into bankruptcy a year later.

Within fifteen years the waterwheel was the subject of picture postcards, which were published to service the rapidly increasing tourist trade brought to the area by the railway opened in Grassington in 1902.

During the Second World War, the level was used as the village air raid shelter, duckboards being placed over the stream for the first 20 metres. It was never used in anger, but locals remember as kids having to retreat there during air raid practices. During the Cold War it was designated the local Civil Defence Shelter, but presumably this was purely nominal.

The level has always had a plentiful stream running through it, and in the 1980s, the local fish farm took advantage of this ready source of water by installing a salmon hatchery. To ensure a constant supply, a 2 metre high dam was built about 85 m in, creating a reservoir some 150 m long. The hatchery was superseded after about ten years, and the dam's outlet pipe was lowered in 2003 to make exploration more comfortable.

Fault Gouge in the First Collapse, December 2012

It had been noted that the level was only accessible for 317 m in 1942, and this was the limit until 2003. At that point, a steeply dipping thick bed of a white powdery material, thought to be fault gouge, had slipped from the roof, and blocked the passage damming the water behind it to the roof. In 2003 this obstruction was dug through by the author and Peter Hodge for about 10 m, lowering the water level beyond. This allowed access for a further 50 metres to a similar obstacle. This too was dug through, and a semi-flooded section with an unstable roof entered. On the first visit the passage terminated in a sump, but when a return was made with diving gear it was found that roof collapses had exposed a further section of passage. A blockage at the end of this was crawled through, but it only led to a ponded section where silt and water reached the roof. This is about 440 m from the entrance, and further progress could only be gained with considerable effort.

A return visit was made earlier this year with Stuart Hesletine, but it was found that in the intervening period bad air had built up in the further reaches, causing breathlessness and giddiness.

In general the current state of the level is good as far as the first blockage, the more unstable sections having been lined. Little in the way of artefacts remain, although in some sections the railway lines are still in place, and the irons inserted into the walls to hold the pneumatic hoses are present throughout.

References and further reading:

- Gill, M.C. (1994). The Grassington Mines British Mining. 46. Keighley: Northern Mine Research Society. ISBN 0-901450-39-1

- Gill, M.C. (1994). The Wharfedale Mines British Mining. 49. Keighley: Northern Mine Research Society. pp. 97–120. ISBN 0-901450-41-3

- Gill, M.C. (1976). A History of the Hebden Moor Lead Mines in the 19th Century British Mining No. 3. pp. 29-34. ISNN 0308-2199

- Joy, David (2002). Hebden The History of a Dales Township Hole Bottom Hebden, Skipton: Hebden History Group. ISBN 0-954304-30-6

- Kingsley, C.D., Wilson, A.A. (1990). Geology of the Northern Pennine Orefield Stainmore to Craven London, HMSO. ISBN 0-118842-84-6

- Raistrick, Arthur (1973) Lead Mining in the Mid-Pennines Truro: D. Bradford Barton Ltd.